The Dunning School of Thought

The subject of my essay will be the Dunning School of Thought. The Dunning School of Thought is classified as period of time between the 1890’s to 1960’s where there was blatant racism in historical scholarship of slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. The Dunning School of Thought can be tracked to William Archibald Dunning: the first Reconstruction historian whose combination of skill, popularity, and charm would elevate his racist historical work to that of archetypical status among the historical community. Dunning’s professor position at Columbia University along with his various roles of leadership in the American Historical Association and Political Science Quarterly would provide the perfect setting for Dunning to amass a large sphere of influence. This influence would propagate in his many students/ disciples who would become the first of many exponentially growing waves of racist scholarship in American history.

When it comes to the history of Reconstruction scholarship – a relatively new field of study- modern historians can track the prevalence of different ideologies into three general categories: the Dunning Era, the Revisionists, and the Post-Revisionists. I intend to primarily focus on the Dunning Era and the resulting consequences of that era for the historical community thereafter. I will define the Revisionists and Post-Revisionists in connection to their role of “fixing” the harm that the Dunning School of Thought instigated. The Dunning Era would completely shape historical biases and methodologies for the field of Reconstruction scholarship for decades. It’s impact, while lessened by the Revisionists and Post-Revisionists, can still be seen today.

William Archibald Dunning was born on May 12th, 1857 in the small town of Plainfield New Jersey to Catherine Trelease and John Dunning. As a young man growing up through the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow, Dunning was exposed firsthand to a rapidly changing political and social era of American history. Dunning attended Columbia University for the duration of his B.A, M.A, and Ph.D and he would continue to work at the university as a professor for the rest of his career.

During his time at Columbia, Dunning studied politics and philosophy under the direct influence of John Burgess, a political science professor, whom Dunning had formed a close friendship with. Burgess was a racist and often taught his classes about “germ theory” in connection to the biological superiority of the founding fathers. Dunning and Burgess would work closely together over the years as Dunning completed his dissertation titled “The Constitution of the United States in Civil War and Reconstruction 1860-1867”. With the publication of “The Constitution” in the Political Science Quarterly (PSQ) in 1886, Dunning’s infamous role in social politics, Reconstruction interpretation, and historiography would begin.

Dunning was the first scholar to write down the narrative that Reconstruction was a ploy by radical Republicans, like Thaddeus Stevens, to take over the southern states and force northern rule over the good people of the south. He argued the south was a victim throughout the war and the emancipation of slaves was just one of many efforts to by the Republicans to gain voters. Dunning did not believe in the inherent equality of man but rather in white supremacy. It was with these principals in mind, that Dunning wove his racism into his writings and began to influence those around him. What was particularly unique to Dunning’s work was his methodology which included clear references to Leopold Van Ranke after Dunning spent a year in Germany following the publication of his dissertation. He applauded Ranke’s source-based methodology, embraced narrative history, and worked with empirical evidence. Burgess, meanwhile, would work with Dunning to discuss “scientific history” and the importance of bias and impartialness to historical work. These methodologies granted Dunning a level of credibility over that of other Reconstruction scholars and his opinion was held in high regard.

Throughout the many essays Dunning would publish till his death in 1922, Dunning was applauded for his incorporation of abundant primary source references as well as commended for the educational value and topical subject during a heightened time of race conflict. Considering the ruling of Plessy V. Ferguson had shaken race-based politics in 1896, Dunning’s writings worked to justify white supremacy and support Jim Crow practices of segregation. Dunning claimed that slavery was the only way the two races would live in harmony and that with the abolition of slavery, the nation was now in a state of confusion that could only be remedied by returning to a system that produced the same racial inequality as with slavery. Research Fellow at the University of Columbia, Tommy Song states, “ When discussing black Americans, Dunning’s scientific method lost relevance, or rather, lost necessity; the professor, now in his forties, believed racial inequality as natural, unworthy of supporting evidence since it was- and should be accepted as- an innate truism.”

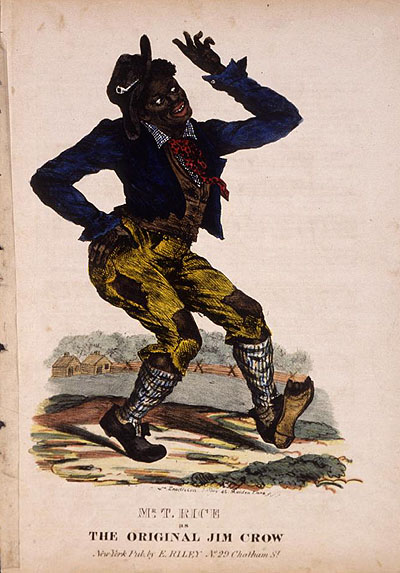

What is unique about the case of William Archibald Dunning, was not his blatant racist views, but rather his “credibility” and large sphere of influence he emitted throughout his life. Unlike other racist scholars of the time, Dunning worked himself into a position of celebrity-like status through the combination of societal timing, topical subjects, hard work, writing skill, and charisma. He used the latest historical methods to provide validity to his work and thus, an air of credibility to himself and his thinking. The contextual timing of Dunning’s work was pertinent to his success as well: the south was arguably still recovering from their loss in the war and societal changes such as the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments brought massive strife to the country nationwide as America struggled to adjust to its new reality. Jim Crow culture shaped many white Americans attitudes towards their black counterparts, and black Americans struggled for basic rights under the ever-present threat of the KKK.

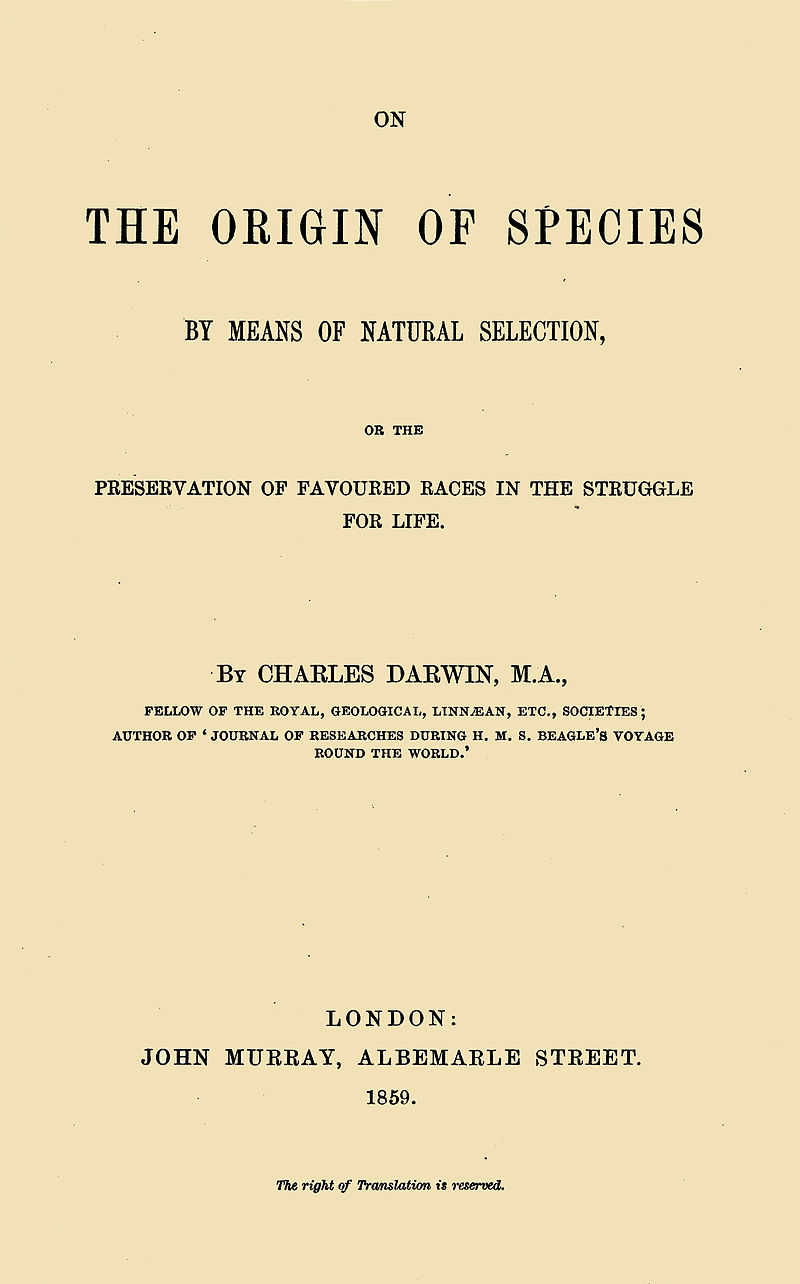

One of the leading rationalizations of Jim Crow and other discriminatory practices towards black Americans was the long-standing idea of Social Darwinism- named after the evolutionist himself, Charles Darwin. The idea of science being able to prove racial inferiority did not originate from Darwin’s work, but Darwin did provide a “credible” source of evidence for those looking to back up their racist claims. Backed by misinterpreting Darwin’s claims, social scientists aruged evolution favored white skin. Social Darwinism was particularly popular in the United States and England -which can be seen in many historical writtings- “because it supported policies and practices that both countries justified as congruent with their national interests.”

For Dunning,scientific racism was an unavoidable cultural sentiment: “During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, scientific racism formed a vital link in the oppression of American blacks. If established social science defined blacks as inferior beings who could naturally be expected to occupy the position in society which they in fact held, the occasional social reformers could be dismissed as romantic dreamers who had neither knowledge nor appreciation of hard scientific fact.”

Dunning affected much of the historical community with his wide sphere of influence which became particularly apparent with his students. Students such as James W. Garner and J.G de Roulhac Hamilton would contribute to historical scholarship of Reconstruction with their own biased writings and eventually become professors themselves among various east coast colleges. Walter L. Fleming would go on to teach at West Virginia University, Louisiana State University, and Vanderbilt University where he continuously spread Dunning’s rhetoric to large masses of students. It was Fleming who predominantly continued Dunning’s work after his death. One of Dunning’s most famous disciples was Claude Bowers, whose primary source of fame came from his book, The Tragic Era: The Revolution After Lincoln, published in 1929. In this work, much like other work presented by Dunning scholars, The Tragic Era propagated southern victimhood, the “Lost Cause” legend, and derogatory stereotypes about black Americans. Yet, unlike Dunning’s own works, which appealed primarily to other Reconstruction scholars, “Bowers’ colorful, fast paced, and dramatic writing style, his apparently thorough research, his ability to draw vivid, detailed portraits of important figures, and his skill at weaving into his story brief quotations from contemporary documents produced a narrative which many found both compelling and convincing. The Tragic Era became a great popular success, reached an audience immeasurably larger than had [Dunning’s work]…” Thus, Dunning would lay the framework but Bowers’ truly spread his rhetoric in what would ultimately accumulate into what Reconstruction revisionist’s would call the Dunning school of thought.

The Dunning school of thought can as such be classified as a predominant ideology that widely sweep through American historical scholarship between the 1890’s to 1950’s. It advocated for white supremacy, southern victimhood, and the “white” experience of slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. Such a legacy would affect more than just its immediate audience: racist histories would influence public perception and media interpretation. No better of an example is D.W Griffith’s A Birth of a Nation which portrayed black Americans as rapists and monsters, and in turn, glorified the KKK as heroes against such horrors. A culture of racism and discrimination would also leak into interview responses as seen directly in the WPA narratives during the Great Depression. Such racism would skew the statistical results of the WPA narratives leading to the infamous account of Fogel and Engerman’s, Time on the Cross, whereby Fogel and Engerman would falsely conclude that slavery “must not be as iniquitous and brutal as formerly portrayed.” At its core, the Dunning school of thought is a period of racist history which affected historical interpretation and methodologies. It backed social inequality by providing “scientific”, “sound”, and “empirical” research that supported segregation and discrimination. Furthermore, framework and methodologies found in the Dunning school of thought was far-reaching: influencing hundreds of historians in one form or another and receiving positive reviews from the public. When reflecting upon Reconstruction historiography, Revisionist historians label this era of historical scholarship: The Dunning Era.

Reconstruction and Reconstruction historiography scholar, Eric Foner, would officially describe the Dunning Era as one of three eras that fundamentally differ from their approaches towards Reconstruction scholarship. The Revisionists would a arrive to the historiographical debate around the 1940s and 1950s inspired by the early writings and protests of W.E.B DuBois and Howard K. Beale who advocated for the black point of view in Reconstruction scholarship. In contrast to the Dunning era, Revisionists “offered sympathetic accounts of the once-despised freedmen, Southern white Republicans, and Northern policymakers.” Of course, such a radical change of view did not happen independently in the minds of a few historians, but rather were the result of “profound change in the nation’s politics and racial attitudes” with the growing build-up to the Civil Rights movement. Foner writes, “In the 1960’s the revisionist wave broke over the field, destroying, in rapid succession, every assumption of the traditional viewpoint” , “So ingrained was the old racist version of Reconstruction that it took an entire decade of scholarship to prove the essentially negative contentions that ‘Negro rule’ was a myth and that Reconstruction represented more than ‘the blackout of honest government’. In essence, Revisionists worked towards correcting the racist wrongs of the Dunning Era and instead presented scholarship that radically contrasted in content. No longer were black Americans vilified. Instead, for the first time in American history, black Americans shared their experience and their version of events en masse. Now their stories were deemed credible and even more important to the study of slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction than white recollections.

But, Foner extends his analysis of Reconstruction historiography into one final division: The Post-Revisionists. As far as present historical thought goes, most historians practicing today would fall into the category of Post-Revisionists. Beginning in the 1970/1980s Foner states, “The post revisionist interpretation represented a striking departure from nearly all previous accounts of the period, for whatever their differences, traditional and revisionist historians at least agreed that Reconstruction was a time of radical change.” Yet, for the Post-Revisionist, historiography was more than just erasing racist sentiment from historical writings. It involved critically analyzing the entire system in light of modern standards. The Dunning Era would label Reconstruction a threat to white America, the Revisionist would applaud the good Reconstruction did for black Americans, and the Post-Revisionist would argue Reconstruction did not go far enough.

Bibliography

Carol M. Taylor, W.E.B DuBois’s Challenge to Scientific Racism.

David E. Kyvig, History as Present Politics: Claude Bowers’ The Tragic Era.

Eric Foner, Reconstruction, America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877.

Fletcher M. Green, Walter Lynwood Fleming: Historian of Reconstruction.

Rutledge M. Dennis, Social Darwinism, Scientific Racism, and the Metaphysics of Race.

Samuel L. Banks, Review: Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery.

Tommy Song, “William Archibald Dunning: Father of Historiographic Racism Columbia’s Legacy of Academic Jim Crow”.

2352 words.