An Untold Story of Rwanda

Rwanda’s Untold Story Documentary by BBC

“The most dangerous histories are those which are believed wholly and without hesitation” - Prof. Fred Gibbs

HISTORIOGRAPHY

This essay will examine the official historical account of the genocide that occurred in Rwanda, 1994, and aim to compare the similarities and differences of how the history of the genocide was written, portrayed, understood, and perceived today. The reality of ‘what really happened’ and the country’s national history of ‘what really happened’ are far from the same. As history is often written and remembered by the victors, a closer examination of the Rwandan genocide reveals a story of government coverups, secrecy, and the suppression of voice by many. Historiography is the study of how history is written, understood, perceived, and interpreted. I will attempt to show how the history of a nation was intentionally manipulated, by the method of partiality, to restore the practical necessity of order within the country.

“Thus, a practically motivated study of something is partial both in the sense that it does not study its material fully but only those ‘parts’ relevant to its objective - and in the sense that the thinking involved demonstrates a ‘partiality’ towards lines of thinking and conclusions appropriate or ‘convenient’ to one’s purposes. Although this does not mean the understandings achieved will necessarily be false (although such a danger threatens), it does mean the study, as angled towards the ends sought, will be ‘distorted” (287). -Lemon

This essay will be constructed in a framework designed to guide the reader in a manner that provides a better understanding of how the ‘history of history’ pertains to Rwanda. It will provide the historical context concerning the genocide, but will focus rather on how we understand the history of the event and how this history effects the nation today. The framework of the essay will be constructed as follows: First, data collection of empirical evidence (primary resources) will be gathered to understand the ‘full’ context. Second, critical comparison of empirical evidence to the historical understanding (official or unofficial) is needed to interpret how the event was perceived and portrayed. Third, understanding how the common believed history of the nation effects the nation today and how a believed history may be used for practical purposes.

Introduction

History often provides people with the perception of a true story, a story all too often perceived to be a close reality of an event or series of events. This essay aims to show how an untold story brings fuller context to the history of Rwanda and how such history underlies a closer ‘truth’ to reality. To study history and come to an understanding closer to that which is truth (as should be the historian’s goal), as well as understanding how history is made to become truth, historiography plays a critical role in determining how we might otherwise understand the history of a country and reach alternative conclusions to that which is often perceived to be history and truth.

Historical Context

The country of Rwanda is a beautiful place full of attractive landscapes, abundance of resources, wonderful people, and exceptionally unique culture. However, aside from these positive attributes, recent events in past decades have unfolded within the country that has resulted in murder, rape, starvation, disease, homelessness, mass genocide, and war crime atrocities.

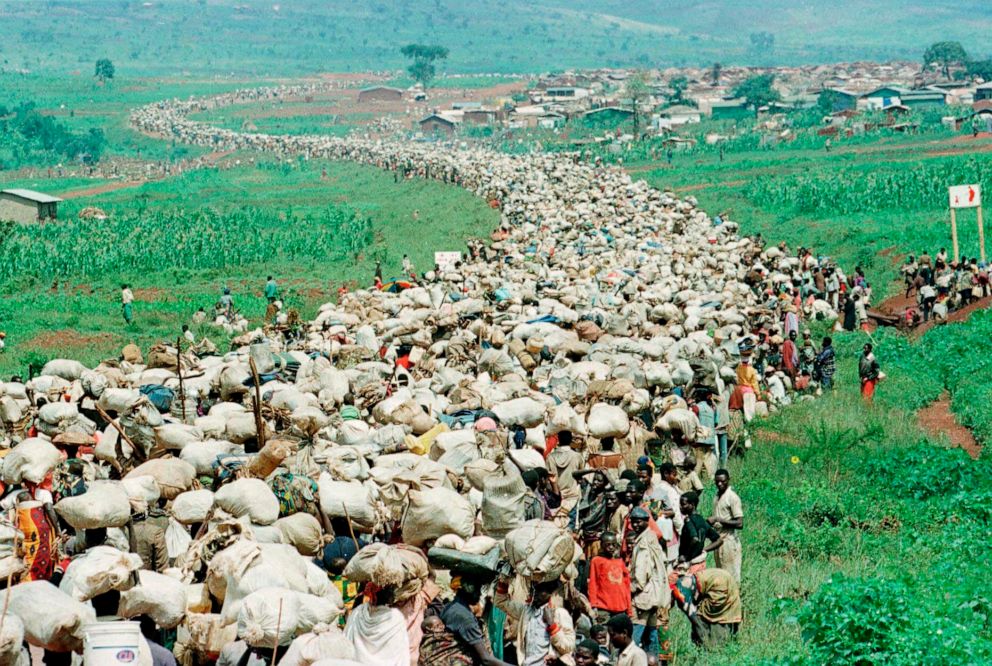

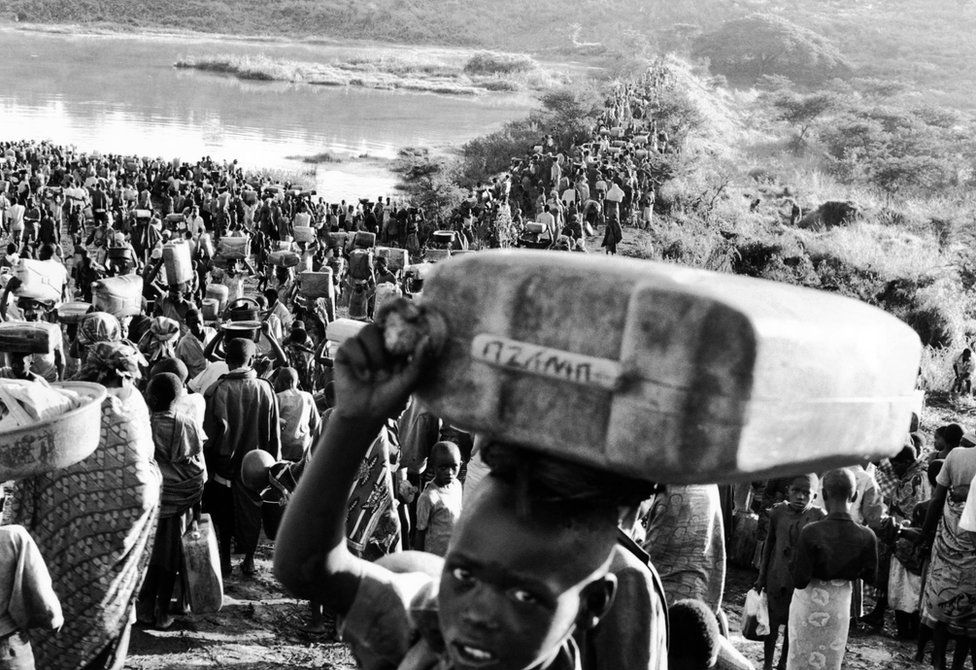

An estimation of approximately 1,000,000 casualties and 5,000,000 refugees have been displaced from their homes in Rwanda as a result of civil war between two opposing tribes, the Hutu and the Tutsi. Tensions and disputes between the two tribes has long withstood, but following the first World War, under the Treaty of Versailles, the League of Nations permitted Belgian occupation of formerly German occupied Rwanda. Belgium, favoring the Tutsi minority over the Hutu majority, gave the tribe special privileges such as western-style education and authority to govern and rule over Rwanda, including governance of the Hutu. This colonial influence of power to the Tutsi tribe largely contributed to the escalation of conflict from dispute to total war between the Hutu and the Tutsi tribes.

Hutu Revolution

In 1957, the PARMEHUTU (Party for the Emancipation of the Hutus) formed to rebel against Tutsi rule. Shortly thereafter, in 1959, the Hutu militia revolted against the Tutsi monarchy and asserted dominance and authority over the country. The Hutu revolution, otherwise known as the “social revolution”, forced evacuation of approximately 150,000 Tutsi people into refugee camps in nearby Burundi and Uganda. The Hutu remained in control of Rwanda for the next 35 years, elected official Juvénal Habyarimana as president.

Rwandan Patriotic Front

In 1988, a counter political party was formed called the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), formed by Tutsi exiles in Uganda. Its goal was aimed to retake control of Rwanda for the Tutsi people. Two years after it’s formation, the RPF invaded Rwanda and fought for control for 3 years until the Arusha Peace Accords were signed on August 3rd, 1993. The peace accords established a cease-fire between Hutu and Tutsi tribes in hopes of coming to diplomatic political negotiations.

Presidential Assasination

On April 6th, 1994, president of Rwanda Juvenal Habyarimana and preident of Burundi Cyprien Ntaryamira (both Hutu), had just boarded a plane that was preparing to take flight when the plane exploded from a rocket propelled grenade launcher. The explosion killed all passengers on the plane. Although the cause of this event was clear to have been intentional, further investigation found no definitive determination of who carried out the plan. However, the assassination sparked outrage amongst Hutu tribesmen within the country who blamed the RPF were responsible for the attack. Hutu militias soon organized and sought to retaliate. Once organized, the Hutu ended the cease-fire and the peace accords ended.

100 Day Massacre

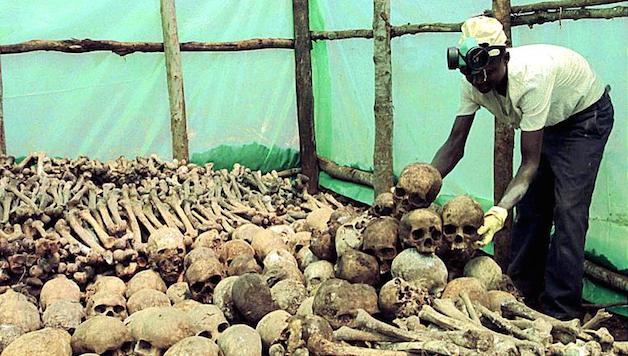

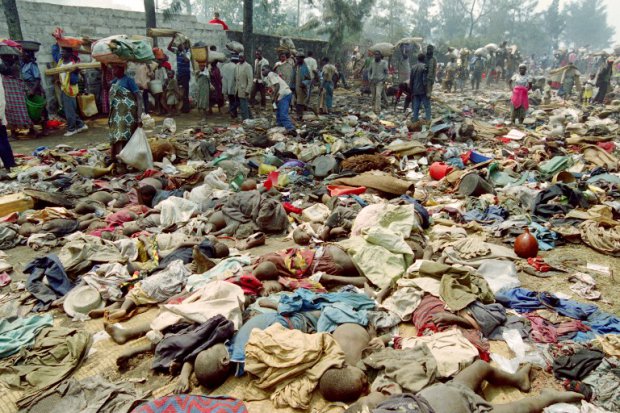

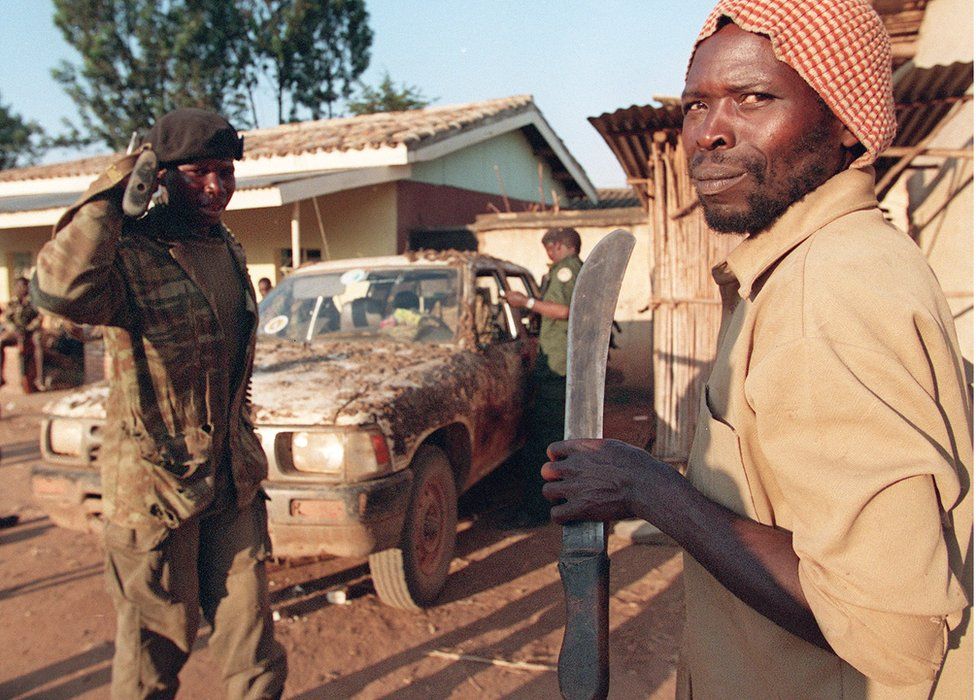

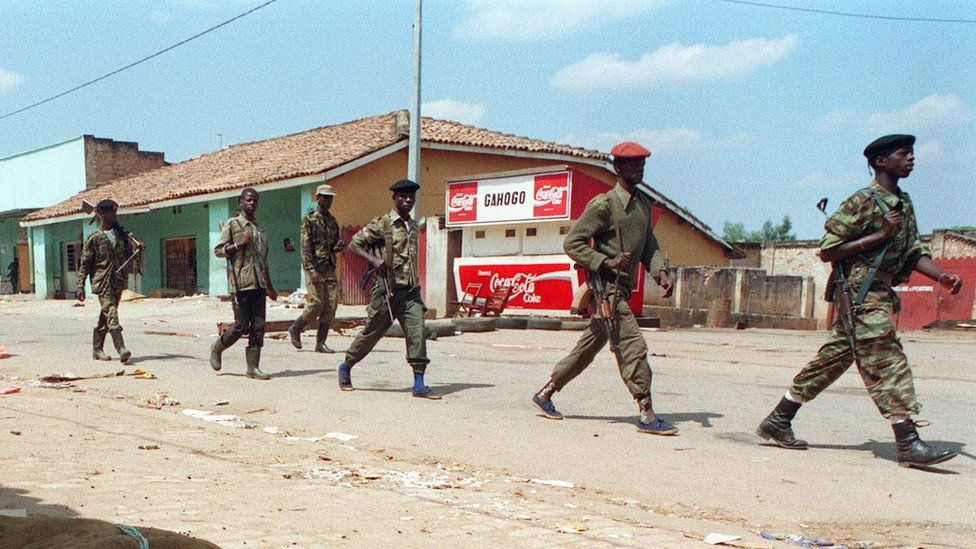

Following the assassination, the National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development (MRND) formed to seek retaliation against Tutsi civilians. A genocide campaign was ordered to seek out and kill all Tutsi members in the country. Roadblocks and blockades were constructed and travelers along roadsides were checked of their tribal orientation based on identification (ID) cards. Any one who was confimred to be Tutsi were shot to death or, in many cases, killed with machetes. Radio broadcasts were transmitted throughout the country to order Hutu members to kill their neighbors. The Hutu militias continued to storm Rwandan cities, successfully capturing most of the countries cities, including the capital Kigali. Within 100 days, approximately 800,000 Tutsi civilians were murdered, raped, and cities pillaged. During this 100 day massacre, Tutsi civilian were indiscrimately targeted including men, women, and children.

RPF Control

In 1990, the RPF led a military coalition against the MRND to retake control of the country. After months of fighting, the RPF began to successfully capture the Rwandan cities. By July 4th, 1994, the RPF captured capital Kigali and on July 18th, 1994, sucessfully gained control of the entire country. The elected president, Paul Kagame, rose to power as the national president of Rwanda and remains president today, 25 years later.

Kibeho Massacre

As the RPF regained military and political control of Rwanda, Hutu tribe members fled their homes in fear of being killed. In south-west Rwanda, Hutu refugees gathered in the Kibeho refugee camp. On April 22, 1995, the Tutsi RPF opened fire on the unarmed refugees began indiscrimately murdering them. Australian soldiers serving as part of the United Nations Assistance Mission later estimated that approximately 4,000 people in the camp were killed. The RPF claimed only 300 people were killed. At the time, current president Paul Kagama was vice president of the RPF.

Restorative Peace

Since the RPF invasion, the country has since reestablished peace and order in the society. President Paul Kagame has been accredited by many of the country’s citizens as the person responsible for reestablishing peace. However, the aftermath shows that criminal offenses and atrocites were caused by both sides and criminal justice for these atrocities was deeply desired.

“By the end of 1994, the human toll of the crisis in Rwanda was in the millions. In addition to the 800,000 victims of the genocide and the two million refugees outside Rwanda, some 1.5 million people were internally displaced. Out of a population of seven million, over half had been directly affected.” -United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

International Criminal Tribunal

In November, 1994, the United Nations establsihed the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. It’s sole purpose was to “prosecute persons responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of Rwanda and neighbouring States, between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 1994”. It has since “indicted 93 individuals whom it considered responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in Rwanda in 1994. Those indicted include high-ranking military and government officials, politicians, businessmen, as well as religious, militia, and media leaders.” This tribunal targetted criminals and made a direct effort to incarcerate the individuals that were responsible.

Presidential Immunity

Paul Kagame was indeniably involved in the delegation of military command connected to the murders that occurred by the RPF in the 1994 invasion to retake Rwanda. He has been accused by many for the assasination of President Juvenal Habyarimana which ended the Arusha Peace Accords and erupted violence and ended the cease-fire. He was also in command of the RPF during the Kibeho massacre. Kagame has denied all accusations agaoinst him and these accusations cannot lead to criminal prosecution against him because of the legal immunity has as president. In 2017, President Paul Kagame won his third seven-year election by a landslide victory recieving over 98.79% of the vote. One of the Kagames political rivals, Diana Rwigara, an outspoken critic of Kagame, was arrested shortly after the election for alleged offenses against state security. Also, Syridio Dusabumuremyi, a political outspoken critic of Kagame from the United Democratic Forces, was suspiciously found dead with his throat cut and stab wounds to his body. No supspect was connected to the murder, but fowl play and political intidation from Kagame has been speculated by many. The cumulation of presidential immunity, fear of persecution on opposing political rivals, and accreditation order restoration to supporters, all help President Paul Kagame establish himself as one who evades justice from genocidal reality due to his power and position. The history that is written and will be remembered of Paul Kagame by those who support him will often be skewed by the reality of his actions and the ability to “play his cards” so that he is remebered as a hero rather than a villain.

Partiality - Remembrance, Memorials, and History

The civil war and human rights violations from both the Tutsi and the Hutu are part of the history of Rwanda in its entirety. Both sides were responsible for war crimes, yet in the country, the genocide is only remembered from a one-sided Tutsi perspective. The Kigali Genocide Memorial website, for instance, expresses clearly the desire to commemorate the victims who suffered, however, it clearly excludes all the victims. The main title states, “WE REMEMBER THE VICTIMS OF THE GENOCIDE AGAINST THE TUTSI AND WE TEACH ABOUT PEACE” This example of partiality shows a direct pattern to historiagraphy of how history is studied, as well as how history and reality are not always the same.

Genocide Denial

Genocide Denial in Rwanda is not the denial that genocide ever occurred, rather, it is the “assertion that the Rwandan genocide did not occur in the manner or to the extent described by scholarship.” In an attempt to cover up the knowledge of secret information and criminal actions by government offcials involved in the genocide, the Rwandan government actively suppresses all public speech that contradicts what their official story is. Any person(s) caught speaking outside what is believed to be the true “history” is considered to be a genocide denier and is subject to incarceration. The article, “Denying Genocide or Denying Free Speech? A Case Study of the Application of Rwanda’s Genocide Denial Laws” examines the country’s laws and attempts to “address a specific aspect of Rwanda’s oppressive political climate: the use of criminal prosecutions under the country’s genocide denial laws to restrict free expression.” it is was determined after examination of the federal genocide denial laws that “Rwanda’s genocide denial laws fail to meet the requisite standard of precision under international law”. I