Eurocentrism

The exact extent of Eurocentrism in contemporary culture, academia, politics, and many other facets of daily life is impossible to determine. While not solidified as a concept until the Postmodern revolution in the late twentieth century, the traces of Eurocentrism throughout history and the deep-seated effects they have had on all human life today are more discussed than ever. Eurocentrism, as a concept, can be applied to any person, place, or thing throughout history; there is truly nothing untouched by Western imperialism and influence. For the purposes of this essay, eurocentrism will focus strictly on historiography, or how history has been written, with a Eurocentric perspective and the repercussions of such views. With this in mind, my examination of Eurocentrism is going to begin with one of the first men considered to be a ‘historian’, Augustine of Hippo. But first, let’s understand exactly what is Eurocentrism.

Eurocentrism: What is it?

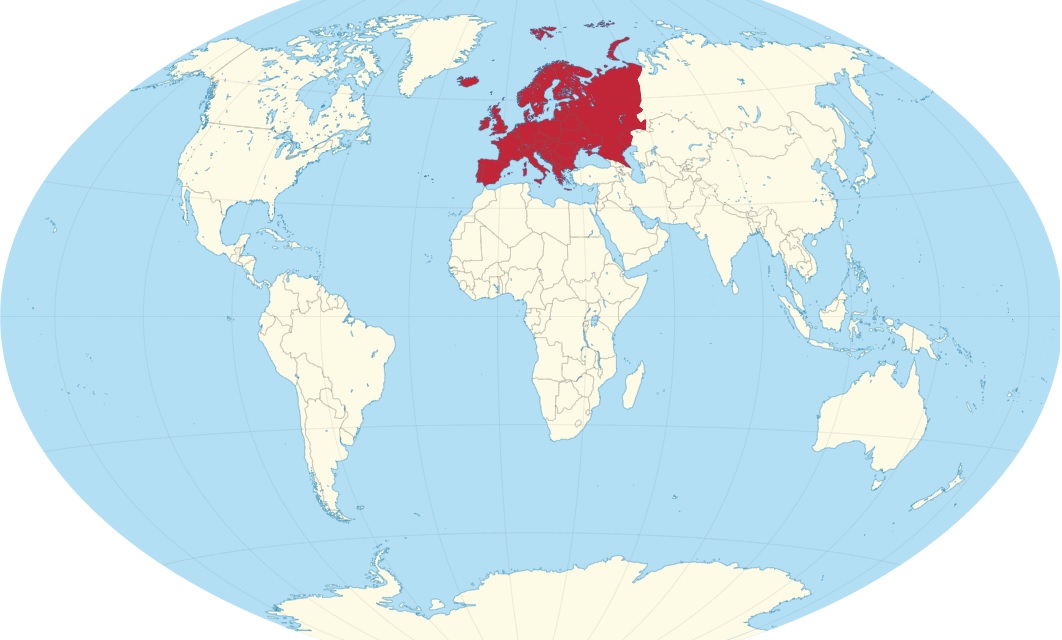

In order to understand eurocentrism, we must first understand a different question: What is Europe? That might seem like an obvious question, Europe is a continent east of the Atlantic Ocean. Geologically, yes, Europe is a continent, but let’s dive into the previous sentence a bit more. “Europe is a continent east of the Atlantic,” why east? How was that orientation determined? Who decided what was east and what was west and from what point? This simple view of our contemporary map is a remnant of a Eurocentric past, drawing Europe as the original focus of the globe.

Inherently, the term ‘Eurocentric’ is easy to parse, ‘euro’ is Europe and ‘centric’ is center. Simply, it is that Europe is viewed and has historically viewed itself as the center of the world, or the focus (more so than the geographical center), and the only ‘west’ before encountering the Americas, naturally designating all other sectors as ‘north’, ‘south’, ‘east’, or ‘west’ from that focal point. But, there is much more to Eurocentrism than locality. Europe is also a concept itself. Much like Eurocentrism, Europe is an idea that a group of people collectively came to understand and agree upon. This idea formed into a culture, with certain values and practices which differentiated it from other cultures, until eventually coinciding with a specific image in our heads of what it means to be ‘European’.

Eurocentrism encompasses many Western concepts (and their very real effects), including colonialism, capitalism, monotheism, racism, patriarchy, and countless other cultural and historical identifiers. However, Eurocentrism itself is not individually any of these concepts, but rather the amalgamation of the hegemonic entity of European culture which through time has influenced the world to such a degree that perspectives have skewed to view Europe as “better”, “more civilized”, “more developed”, or as a “First World” in comparison to non-European regions. Eurocentrism has acted as both the motivation for and the outcome of many of these listed concepts, giving it its complex, multilayered identity.

Origins to Present

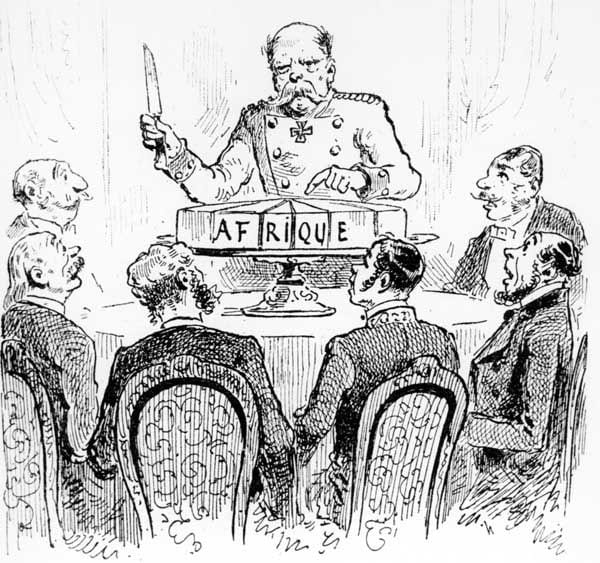

Many authors of Eurocentrism trace its origins as far back as ancient Greece, acting as a continental “crossroads” between Europe, Africa, and Asia, and an origin of textual historical documents. For centuries, the Mediterranean was seen as not only the origin of European culture, but as the origin of humans themselves, civilization, democracy, and philosophy. With a political system based on imperialism, that is, expanding of an empire, and colonialism, the control or occupancy of another government, it is clear that a foundation for Eurocentrism began in Greece. However, Eurocentrism today has a much more complicated interaction with the world which is more closely linked to the late Roman period, around the fifth century.

Fun Fact: The term “Barbarian” is actually a Greek term used to describe anyone who did not speak Koine Greek, the common language in ancient Greece. ‘ian’ means “one who speaks” and ‘bar’ describes what Grecians thought non-Greek languages sounded like, “barbarbarbar”.

In response to the Roman defeat by the Visigoths in 410CE, Bishop Augustine of Hippo wrote a document titled City of God. His intention was to explain the reasons for Roman defeat and attempt to understand human history, as well as predict the future fate of humanity (Fortin, 324). However, as historians, we can examine this document for much more than its intended purpose. Augustine redefined history as not only a Western one, but as a Christian one. This is a belief that will become the basis for contemporary Eurocentrism, much more permeating than the Greeks ever employed. With the addition of Christianity to Western, European identity, the concept of paternalism, or Europe viewing itself as a ‘father’ to the rest of the world, soon intertwined with this identity. Already well-developed in the Roman-Catholic church (think of the male-dominated clergy, such as the Pope, archbishop, bishops, etc., roles which can only be held by males and the view of the Christian god himself as a man and father), paternalism offered a new understanding of Europeanism that not only provincialized all non-European countries, but also positioned them as children needing to be cared for by their European ‘father’.

Pro.vin.cial, adj.: of or concerning the regions outside the capital city of a country, especially when regarded as unsophisticated or narrow-minded. Provincialism refers to the byproduct of Eurocentrism. While Europe positioned itself as the center of the world, all other countries were ‘provincialized’, or seen as on the “outskirts” of history, rather than as active participants. Additionally this view strengthened European ideas of non-Europeans as ‘children’, who were uneducated, pagan, ‘backward’, and in need of assistance, or being ‘saved’.

Historians today are able to study events in the past and understand them as Eurocentric, but why did it take so long for this to become a part of historiographical and social discussion? In the late twentieth century, a movement began known as ‘Postmodernism’, in response to ‘Modernism’ which believed in universalities and metanarratives as useful techniques for understanding cultures around the world. On the other side, Postmodernism sought to ‘break down’ all of the ideas of Modernism and establish that all people had different views of ‘reality’ and no one reality could be seen as the only ‘true’ version of events (Popkin, 146). Today, this is now a much more common understanding of history, but it is still a relatively recent view and application by historians.

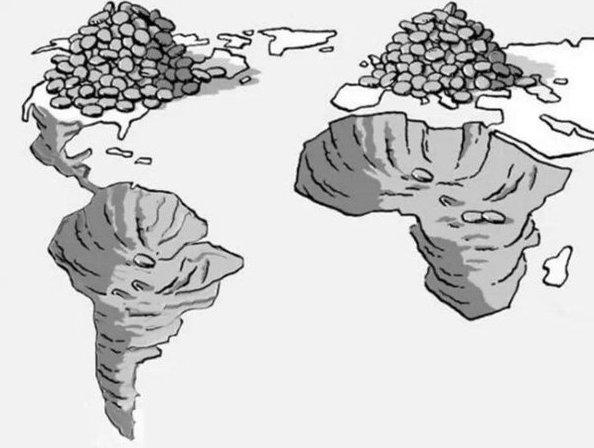

One theory of why this view at last took hold in the twentieth century is due to what Chinese historian, Robert B. Marks, refers to as “the Gap” (Marks, 5). By the twentieth century, the economic gap between “first” and “third” world countries had become so severe and obvious that the direct and indirect effects of colonialism could no longer be denied or hidden. While countries with the highest populations, such as India and most African countries, had the lowest annual incomes and revenue, countries with much smaller populations, such as England or United States of America, earned the highest annual incomes and revenues. These distinct differences in quality of life caused many historians to retrace the past in order to understand why these gaps had occurred. As a result, terms like hegemony, anti-colonialism, and Eurocentrism made their way into mainstream discussions. Eurocentrism has expanded to include North America, today, and can also be called “Americentrism”.

Examples of Historiographical Eurocentrism

Eurocentrism in Textbooks and the “Discovery” of the “New” World

How did you learn about the history of Mexico and South America in your high school history class or early college courses? Were Europeans portrayed as heroes, or saviors? How highlighted were the genocides which decimated over ninety percent of the indigenous populations? (Hamnett, 82) Was any indigenous context or point of view discussed? These are the types of questions Historiographers have asked since Postmodernism. What was happening on the “other” side of history? But, also, how has the history of Europe and the “other” been portrayed and reinforced through Western education? History textbooks do not only lay a foundation for education and a basic understanding of history, but can also be used to propagate Eurocentric ideas (Paez, 211-217). These views of European history can further create a divide between Europe and the “other” by generating an “Us vs. Them” mentality (Shohat, 61).

By now you are probably well aware that the term “Indian” to refer to some indigenous Americans is not only inaccurate, but also inappropriate, but there is so much more than just a misnomer that has portrayed indigenous Americans inaccurately. While the term “Indian” was a colonial invention, so was the idea of an “Indian” (Bonfil-Batalla, 79). There was no specific identity or trait that indigenous groups used to describe themselves collectively. There were hundreds (if not thousands) of independent tribes which all identified themselves as different from one another as the English and Scotts. It was not until Spanish arrival that “Indians” were lumped into one identifying category, without acknowledgment of their various cultural differences. Today, some tribes have chosen to reclaim the use of the term “Indian” while others have renamed themselves, such as the Pueblo Indigena, “Original People”, in Latin America (Jackson and Warren, 557).

Finally, let’s discuss Christopher Columbus. It is a popular question, whether Columbus Day should be celebrated, but I want to focus more so on the specific language we use to talk about him at all. In 1992, the Mexican government changed the “Discovery of America” to “The Encounter of Two Worlds”, an idea which still celebrated the meeting of European and indigenous cultures, but removed the implication that America was something waiting to be “discovered”, rather than a whole, functioning region on its own (Pena, 286). Likewise, the Americas being referred to as the “new” world, aid Eurocentric sentiments that indigenous groups lack a substantial history of their own or that their presence was little recognized at all when colonists arrived. Indigenous American people have a history as long and complex as Europe, as can be said for all regions around the globe.

Eurocentric Ideology and the Imposition of Progress

Progress is one of the most overriding Eurocentric concepts which has impacted not only our views of “othered” regions, but has actually impacted their real-world ability to participate in valued (meaning Western) economics, academia, and politics. Western ideas of progression, meaning a continuous improvement of building ideas and inventions over time, has effected countless regions and Eurocentric views of them as ‘stagnant’, ‘immobile’, or ‘unproductive’. Essentially, when it comes to the ‘progress’ the West has made, it entirely rejects any historical contribution by non-European regions (Demir, 79). Have you taken the required course “Western Civilization” yet? What does ‘civilization’ even mean? It’s a European concept to describe aspects of European society. So, any culture which defines progress differently, or not at all, is viewed as ‘uncivilized’ and, therefore, not part of European history.

So, what about cultures that do have ideas of progress, but they are the exact opposite of Western ideals. What about cultures that pride themselves on caring for the earth and not creating waste? Or cultures which value concepts of community sharing and reciprocity over individualism and mass economies? How can cultures like these ever make their way into the vision of a world history rather than a Western history?

Eurocentrism in Multimedia

While you might not think of movies, television, or even music as a form of history, these portrayals of Western culture and history are just as, if not more so, important to the reinforcement of Eurocentric beliefs. Not only are these resources accessible to Westerners, but they are accessible around the world. Eurocentric idealizations not only reinforce western beliefs of superiority, but are also used to reinforce “other’s” views of themselves as inferior. Can you name one film where America is portrayed as the ‘villain’, rather than the hero? Further, historical films are used to depict issues as only in the past, rather than continuous scenarios with long-lasting repercussions for all involved (Lambropoulos, 194). For example, a historical film which depicts slavery as “ending” does not really mean that the effects of slavery have ended, but can give that impression to a viewer who does not live with those historical impacts. This can create a conversational boundary between a European who views history and a non-European who lives with history.

For some examples, view these articles on Black Panther (Note the authors):

Black Panther: does the Marvel epic solve Hollywood’s Africa problem?

Black Panther review – Marvel’s thrilling vision of the afrofuture

So, Now What?

While Eurocentrism can feel like a weight of centuries of history you had no control over, it is important to recognize the impact that your voice can have today. As a historiographer, or historian, it is not your job to ‘correct’ the past, but rather to attempt to understand it and explain it to others. By placing an emphasis on the voices of those “othered” by European history, historians are working to collect a more diverse, less Eurocentric contemporary history. This is as much an effort for today’s readers as a hope that future historians will not have the same constraints when conducting research. There is no cure or quick-fix for Eurocentrism and no way to undo the effects it has had on all societies over time, but through historiography there are ways to analyze and critique its usage and influence its direction in the future.

In an effort to support the expansion of perspectives, the majority of sources for this essay were written by non-Europeans, non-Christians, and/or women.

https://keenahays.github.io/intro-guide/essays/thematic/eurocentrism

2508 words.