Fernand Braudel

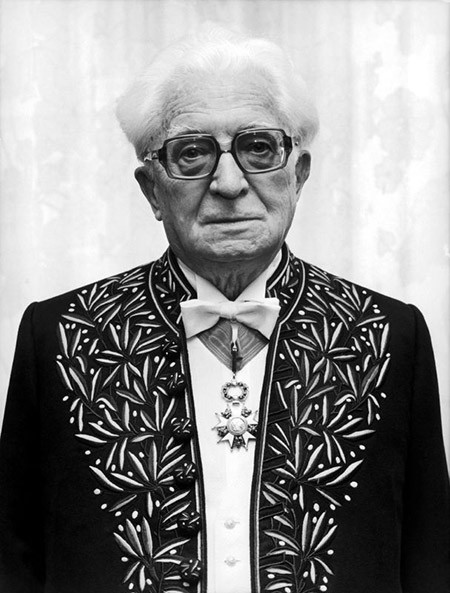

Fernand Paul Braudel was many things. One of them was a historian who rejected the significance of individual people and events. He worked for more than fifty years advocating history “based on a consideration of physical and material constraints, one in which the individual was subsumed by the environment” (Hufton, 209). What would he think of someone writing his story, searching for meaning in the course of his years instead of in the landscapes he inhabited? How should I honor his life and remember his work in the face of such irony? Here goes—honestly, self-reflexively, and with a wry nod to the absurdity of this conundrum.

HIS LIFE

Early Years

“I was in the beginning and I remain now a historian of peasant stock.” (Braudel, 449)

Fernand Paul Braudel was born on August 24, 1902 in Lumeville, a humble village of two hundred people in north eastern France. Raised from an early age by his paternal grandmother, Braudel moved to the outskirts of Paris in 1908. While his father taught in the city, Braudel attended first the Lycee Voltaire and then the Sorbonne, where he got a degree in history “without difficulty, but also without much enjoyment” (Braudel, 449). Braudel noted the instruction of French economic historian Henri Hauser as “his one agreeable memory” (449) at the Sorbonne. Braudel’s upbringing in the countryside—where he experienced first hand the influence of things like crop cycles and weather patterns on the history of his village—provided the foundation for much of his geographical historical perspectives later in life.

Algeria and Brazil

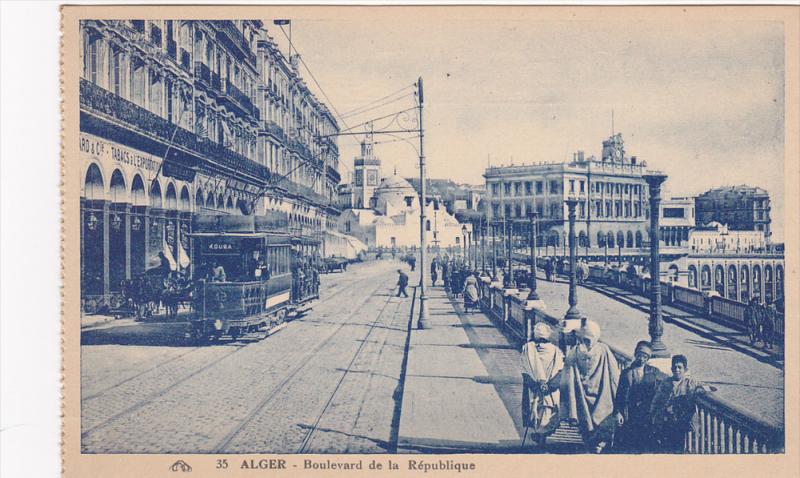

“I believe that this spectacle, the Mediterranean as seen from the opposite shore, upside down, had considerable impact on my vision of history.” (Braudel, 450)

Upon graduation, Braudel was assigned a position teaching history in Constantine, Algeria. As a man in his early twenties, Braudel delighted in the city, the Sahara, and in teaching, despite the fact that he was instructing his students “a superficial history of events…of happenings, of politics, of great men” (Braudel, 450). In the summers, when school was not in session, Braudel spent countless hours at the archives working on a thesis surrounding King Phillip II of Spain. Using an old film camera he purchased from an American cameraman, Braudel took upwards of 2,000 photos a day of documents in the archives, inadvertently becoming “the first user of microfilms” (Braudel, 452). This methodology alone changed the way professionals and novices alike do history, but that was only the beginning. His time in Algeria challenged his Eurocentric view of world and opened his eyes to influences on the other side of the Mediterranean.

In 1935 Braudel accepted a teaching position in Sao Paulo, Brazil. For three years he taught a course on the history of civilization and continued his work in the archives. Braudel claimed that from Brazil “he could see the Mediterranean from outside as a whole” while also getting a glimpse into the past by observing the “still surviving forms of social control and modes of exploitation of the land and of the labor force” reminiscent of Medieval Europe (Aymard, 18).

Another significant result of Braudel’s time in Brazil was his introduction to the renowned French historian Lucien Febvre in October of 1937. Both men were on board a ship heading back to Europe, Braudel after teaching in Sao Paulo and Febvre after lecturing in Buenos Aires. After twenty days on the water together, Braudel had become “more than a companion to Lucien Febvre…a little like a son (Braudel, 452). By 1939, after more than a decade in the archives, Braudel was ready to start writing his book on the Mediterranean. That same year he but was called to serve in the French army.

As a Prisoner of War

“Had it not been for my imprisonment, I would surely have written quite a different book. For prison can be a good school. It teaches patience, tolerance.” (Braudel, 453)

From 1940 to 1945, Braudel was a prisoner of war in Nazi Germany. He served at two separate camps—Mainz and Lubeck—finding solace in his writing and in lecturing to fellow prisoners. In his Personal Testimony, Braudel writes of the impact that the burden of time and the times had on his historiographical approach. “My vision of history took on its definitive form without my being entirely aware of it…partly as a direct existential response to the tragic times I was passing through” (Braudel, 454). He was able to survive the horrors of the world around him by denying the importance of individual occurrences in favor of histories written around longer time scales. During this period, Braudel wrote “600,000 words of text from memory” (Hufton, 208) on school notebooks he sent out to Febvre. These would become the draft of his magnum opus, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Time of Phillip II, the book that would define not only the rest of his life but also a shift in 20th century historiography.

Professional Life

The companion article on this site titled “The Annales School” details the influence and implications of these French thinkers; however, the Annales deserves additional attention here for Braudel’s role in its second wave. Braudel worked under Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch, the original founders of the Annales journal that would inspire the movement, upon returning from Brazil. His association with Febvre continued even during his time as a prisoner of war as Braudel sent draft after draft of The Mediterranean to Febvre for safekeeping and review. With the publishing of that work in 1949, Braudel gained widespread notoriety and became the preeminent historian in post-war Europe. Following the death of Febvre in 1956, Braudel took over as director of The Annales. In 1968, “he entrusted his editorial responsibilities to a younger generation of historians…but maintained officially up to his own death the direction” (Aymard, 14) of the Annales.

Outside of his time with the Annales, Braudel worked as a professor at the College de France, served as “president of the VI section of the Ecole Pratique de Hautes Etudes, and director of the Masion de Sciences de l’Homme” (Hufton, 208). All the while he continued work on a 1966 revision of The Mediterranean as well as a massive new history on Capitalism which he would publish in 1967 under the title Civilization and Capitalism. The Identity of France, published posthumously in 1986, examines the history of Braudel’s motherland and is our final glimpse into the mind of “the greatest and most influential historian of our time” (Hufton, 208).

HIS LEGACY

“In his very person he became a living legend, the incarnation of the historical energies of two, if not three, generations of historians, and a dynamic creative force.” -Olwen Hufton

The Mediterranean

What began as a thesis on the life of King Phillip II of Spain ultimately became a thousand plus page discussion on the history of the Mediterranean using a “tripartite notion on which common time was set on one side” (Hufton, 112) so that the long duration effects of geography, climate, and sociology came to the forefront. The Braudelian perspective of time centered around the idea that all historical events could be examined in distinct time scales: the longue duree, the moyenne duree, and the courte duree. “The longue duree, virtually boundless time, perhaps extending over centuries of common time during which the parameters of human existence were unchanged” (Hufton, 112) was the most influential scale according to Braudel. The moyenne duree relates to “anything in common time perhaps from fifty years to a century” (Hufton, 112) where shifts in trade cycles or urban development are witnessed, for example. Finally, the courte duree refers to “phenomena such as abnormal harvests or short industrial slumps or temporary dislocation which might…be the product of war, occupation, etc.” (Hufton, 112). In the case of The Mediterranean, Braudel tells the story of life during the era of King Phillip from all of these time scales to “teach how, in the lands around the ever-changing and never-changing sea, time and space, history and geography together shaped one coherent past, present, and future” (Marino, 649). His emphasis on the longue duree devalued individual people and events, drawing some criticism from his contemporaries who focused largely on political history and biography.

Capitalism

Methodology and Writing